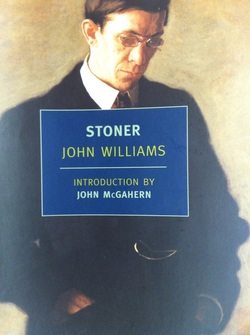

Author: John Williams

Publication Date: 1965

How I Heard About It: Recommended by a friend

Ah, the English Professor, that perennial subject of the biopic, stumbling cliché of alcoholism and existential emptiness, too self-conscious for his (rarely her) own good. You have probably seen them: Wonder Boys, The Squid and the Whale, A Single Man, Smart People, etc. etc.

It’s not that these portrayals are necessarily false. It’s that most of them (but not all) are lousy films.

John Williams’ 1965 novel, Stoner, is about an English professor who is not an alcoholic. Nor is he, as one might believe the title to imply, a pot-smoker. His name is William Stoner, and this quietly beautiful novel chronicles his career at the University of Missouri in the first half of the twentieth century.

We learn on the first page, in a remarkably bleak sentence, the tragic fate of our title character:

Stoner’s colleagues, who held him in no particular esteem when he was alive, speak of him rarely now; to the older ones, his name is a reminder of the end that awaits them all, and to the younger ones it is merely a sound which evokes no sense of the past and no identity with which they can associate themselves or their careers.

The nod here, I think, is to another chilling portrait of human isolation—Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilych, which contains this more blatantly ironic passage on its first page:

So on receiving the news of Ivan Ilych's death the first thought of each of the gentlemen in that private room was of the changes and promotions it might occasion among themselves or their acquaintances.

This kind of announcement relieves us of surprise. It’s not if our character dies. Only when. And thus what emerges between the casual mention of Stoner’s death at the beginning of the novel, and the haunting and intricate details of his death at the end, is the embodiment of what Arthur Miller called “Tragedy and the Common Man.”

For William Stoner’s life is nothing if not a series of disappointments. Remarkably, though, he does not emerge as a pathetic character in the way that, say, Willy Loman does.

Partly this has to do with the calmness and clarity of Williams’ prose—what you might say is its iciness, and thereby its incisiveness—and the way that his prose mirrors Stoner’s demeanor. Stoner is not hyperactive or manic like Willy Loman. His problems are serious, to be sure, but he confronts them with a clear control of emotion. And thus Williams charges the atmosphere with awkwardness and tension.

Take, for instance, Stoner’s decision, against the wishes of his humbly rural parents, to study literature rather than agriculture. But he does not tell them until they make the long trek to Columbia for his graduation:

They were alone in the kitchen…But neither then nor after his parents had finished breakfast could he bring himself to tell them of his change of plans, of his decision not to return to the farm. Once or twice he started to speak; then he looked at the brown faces that rose nakedly out of their new clothing, and thought of the long journey they had made and of the years they had awaited his return. He sat stiffly with them until they finished and came into the kitchen. Then he told them that he had to go early to the University and that he would see them there later in the day, at his exercises.

He cannot here, as elsewhere, bring himself to speak his mind. Indeed, this is often a novel of long silences. Not until halfway through, during the first of Stoner’s academic scandals, do we get any detailed discussion of literature.

Instead, the novel traces Stoner’s increasing detachment from the big things in life: his marriage, his family, his career, his search for meaning.

Williams reserves the novel’s most stinging portrait for Stoner’s wife, Edith, who must surely be among the coldest bitches in all of literature. Though her bitchiness, at times, seems a bit one-dimensional (there really isn’t any gray area with her), at least you can say this about it: it is absolutely relentless.

Even on their honeymoon you can predict their unhappy destiny:

When he returned, Edith was in bed with the covers pulled to her chin, her face turned upward, her eyes closed, a thin frown creasing her forehead. Silently, as if she were asleep, Stoner undressed and got into bed beside her. For several moments he lay with his desire, which had become an impersonal thing, belonging to himself alone. He spoke to Edith, as if to find a haven for what he felt; she did not answer. He moved his hand upon her; she did not stir; her frown deepened. Again he spoke, saying her name to silence.

The silences here are Edith’s, not Stoner’s, and they contrast with her nearly manic, though honest, remark at his deathbed. She says to one of Stoner’s dean, his only friend Gordon Finch (and not to Stoner; no, never directly to Stoner): “‘He looks awful. Poor Willy. He won’t be with us much longer.’”

Small wonder Stoner never turned to alcohol after all. What he turns to instead is his work, and John Williams has been quoted as saying, “The important thing to me is Stoner’s sense of a job.” As Edith takes an extended vacation in St. Louis after her father’s suicide, Stoner realizes his marriage is a failure but that his

love of literature, of language, of the mystery of the mind and heart showing themselves in the minute, strange, and unexpected combinations of letters and words, in the blackest and coldest print—the love which he had hidden as if it were illicit and dangerous, he began to display, tentatively at first, and then boldly, and then proudly.

But disillusionment, as it tends to do, grows. Edith plays mind games with their daughter, Grace, and turns her quietly against him. An annoying and incompetent graduate student receives an F in one of Stoner’s classes, sides with the incoming department chair, and hinders Stoner’s career.

And like all serious writers and scholars, Stoner begins to doubt his vocation. And the doubt, by turns, hardens and softens him. Picture him with the Buddha’s half-smile in the following lines, which characterize despair quite beautifully:

He took a grim and ironic pleasure from the possibility that what little learning he had managed to acquire had led him to this knowledge: that in the long run of all things, even the learning that let him know this, were futile and empty, and ta last diminished into a nothingness they did not alter.

But then, like a false spring, Stoner falls for a younger instructor named Katherine Driscoll, and we never doubt for a moment that they are in pure, true love. They read together, make love often, even vacation in a cabin during one chilly winter break. And here, too, Stoner has an epiphany about love that becomes itself a kind of love poem, and that needs to be quoted in its entirety:

In his extreme youth Stoner had thought of love as an absolute state of being to which, if one were lucky, one might find access; in his maturity he had decided it was the heaven of a false religion, toward which one ought to gaze with an amused disbelief, a gently familiar contempt, and an embarrassed nostalgia. Now in his middle age he began to know that it was neither a state of grace nor an illusion; he saw it as a human act of becoming, a condition that was invented and modified moment by moment and day by day, by the will and the intelligence of the heart.

Needless to say, this is beautiful prose. But by now—on page 195 of a 278-page novel—we know the outcome. Stoner’s rival colleague, Hollis Lomax (another one-dimensional character, and a categorically imperative asshole) sees to it that their love affair ends.

Stoner grows even more disillusioned and then, years later but seemingly as a result of Katherine’s absence, fatally ill. And if you think I have spoiled the ending, then this novel is not for you. One comes to this novel not for its plot but for its beautiful prose and its quiet passages of stoic solitude. And nowhere is Williams better than in describing Stoner’s last moments on earth, in its illuminated details—“The sky outside, the deep blue-black space, and the thin glow of moonlight through a cloud,” “the distant sound of laughter,” “the sweet odors of grass and lead and flower”—and in which Stoner picks up one of his old books:

It hardly mattered to him that the book was forgotten and that it served no use; and the question of its worth at any time seemed almost trivial. He did not have the illusion that he would find himself there, in the fading print; and yet, he knew, a small part of him that he could not deny was there, and would be there.

One can’t help but wonder, especially if one is in the profession, whether or not Stoner’s story is the story of all English professors or writers. But it is not. No more than any of the lousy movies about English professors are. This is a story, in the end, about all of us.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed