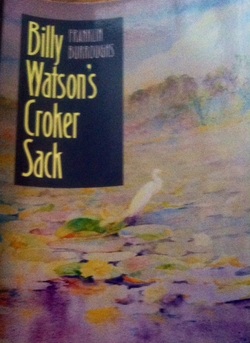

Title: Billy Watson's Croker Sack

Author: Franklin Burroughs

Publication Date: 1991

How I Heard About It: LIterary Osmosis

“I very much fear,” Franklin Burroughs writes at the end of his last (and title) essay in Billy Watson’s Croker Sack, “that writing about such a place will come out sounding like ‘local color.’ …[But] I’m sure my writing won’t consistently escape these evasions of the complexities of the particular place, or of the self that looks at it. But the croker sack has quite unexpectedly turned out to be an emblem of what I would hope to find and how I would hope to find it.”

What we find in these six essays, as if opening a croker sack[1], epitomizes the very best of (pardon the term) nature writing—the insightful and complex intersections between human and natural history, the precision of language and image. The places that Burroughs writes about in Billy Watson’s Croker Sack are either the Maine of his adult life or the South Carolina low country of his youth, more often the connection between the two.

So if it’s local color, I like local color, and damn those who don’t. In fact, it’s no secret that I’ve always admired and envied Burroughs, if not felt a kind of kinship with him. We both were born in South Carolina, both graduated as English majors from Sewanee. During my Maymester kayaking and writing course, I taught his book The River Home, which chronicles his canoe trip down the Waccamaw River in the wake of a writer named Nathaniel Holmes Bishop, who made a remarkable 2500 miles journey in a paper canoe from Quebec to the Gulf of Mexico from 1874-1875, and who wrote about it in a book (an obscure one!) called The Voyage of the Paper Canoe.

And, indeed, Burroughs’ prose has an ease to it that can only be described in the metaphorical terms of a river—an ability to flow effortlessly between the personal, the political , the scientific, the historical, the journalistic, the ethical, the philosophical, the etymological, and so forth.[2]

Take, for instance, the first essay in the collection, “A Snapping Turtle in June,” in which Burroughs finds a snapping turtle digging a hole on a road in Maine. The discovery leads him, as writer, into marvelous description:

The shell and skin are a muddy gray; the eye, too, is of a murky mud color. The pupil is black and shaped like a star or a spoked wheel. Within the eye there is a strange yellowish glint, as though you were looking down into turbid water and seeing, in the depths of the water, like light from a smoldering fire. It is one of Nature’s more nightmarish eyes…The snapper’s eye is dull, like a pig’s, but inside it there is this savage malevolence, something suggesting not only an evil intention towards the worlds, but the torment of an inner affliction.

I did not intend, when copying that just now, to quote that much of the text. But each sentence, as you will note, surged with a new intensity.[3]

The literary father here, of course, is Thoreau. One cannot think of a New England nature essayist, even a South Carolina transplant, without thinking of Thoreau, who, more than Emerson, wrote essays that moved so easily between narrative and meditation.

But back to snapping turtles.

It’s not just description that carries this essay—it’s also the fact that Burroughs is a meticulous researcher. And he can relate his research to the non-scientific reader: “The fish they catch by luring them into range with their vermiform tongues, which may have something to do with the role of trickster that they assume in the mythology of North American Indians.”

And then Burroughs will step back and narrate the story of showing the turtle to his young daughters and of carrying the hissing turtle from road to ditch. And then, as though reaching farther down into the croker sack, he’ll pull out the real story—a flashback to his boyhood in Conway, a summer in which he works for a timber company with his two cousins[4].

It’s in this memory that something terrible and strange happens when a drunk—sitting in a country store where the timber crew is having lunch, and mumbling incoherencies about a man named McNair—suddenly explodes and takes out his rage on a snapping turtle that is something like the store’s houseguest:

The turtle seemed weary, deflated, too long out of water. The man nudged its head with his boot, and the turtle hissed and struck feebly toward him. The man glared down at it, letting his rage recover and build back in him. He looked like a diver, gathering to plunge. The turtle’s mouth hung open, when it hissed again the man’s arm suddenly jerked down with the pistol and he shot it, shattering the turtle’s head. ‘That’s what I’d do to that goddamned McNair.’

Burroughs doesn’t end the essay there. He returns, of course, to his daughters, who are made more innocent in contrast with the violent memory. But the episode haunts the reader in a way that it must haunt Burroughs himself, and one sees the very fluid connection between Nature and Human.

I won’t spoil the rest of the essays as I might have here. But it’s fair to say that Burroughs treats the rest of his subjects—moose, fishing, dogs, duck hunting, the croker sack itself—with the same range of complexity and beauty as he does the snapping turtle.

There is, perhaps, a limited readership for a book like this, but I am in it. My interest is partly local, partly personal, but mostly because of the gorgeous writing, both on the sentence and thematic level, that just flows.

At the end of “Of Moose and Moose Hunter,” Burroughs has a kind of flash forward to a moment that hasn’t happened yet, but will, when he sees a moose while fly-fishing, and how he describes it might be exactly how one feels about reading this book:

And I would look up from the water, almost dizzy with staring for so long at nothing but the tiny fly drifting in the current, and there they would be—maybe a cow and a calf—standing on the other bank, watching me watch them, trying to fathom it.

[1] Burroughs: “In South Carolina the word referred to any biggish cloth sack—for example, the hundred-pound sacks that livestock feed came in.”

[2] Burroughs also has an amazing vocabulary that he employs with ease. In one paragraph alone he uses the following words casually and in a way that doesn't suggest, in my opinion, pretense: frowsy, parataxis, importunity, and furtive.

[3] “The image is Zen,” the poet Charles Wright writes. “The metaphor is Christian.” If so (and I do believe so), in the quoted passage above you’ll notice the Zen-like attention to detail but also the subtle ways in which Burroughs converts images to wonderful metaphors. And that, I think, may be a valid way to describe Burroughs as a writer—he never makes any outright statements of faith, but his writing is imbedded with an intellectual Christianity (a.k.a. Episcopalianism).

[4] Burroughs is also, I might add here, a master of character description: “He was lanky, with comically large feet and big, bony, lightly freckled hands and wrists, and you would have expected him to have no strength and stamina at all. But he could use any of the tools we used—bushaxe or machete or grubbing hoe—with no sign of strain or fatigue, all day long, holding the tool gingerly, a pace that the rest of us could not sustain.”

Author: Franklin Burroughs

Publication Date: 1991

How I Heard About It: LIterary Osmosis

“I very much fear,” Franklin Burroughs writes at the end of his last (and title) essay in Billy Watson’s Croker Sack, “that writing about such a place will come out sounding like ‘local color.’ …[But] I’m sure my writing won’t consistently escape these evasions of the complexities of the particular place, or of the self that looks at it. But the croker sack has quite unexpectedly turned out to be an emblem of what I would hope to find and how I would hope to find it.”

What we find in these six essays, as if opening a croker sack[1], epitomizes the very best of (pardon the term) nature writing—the insightful and complex intersections between human and natural history, the precision of language and image. The places that Burroughs writes about in Billy Watson’s Croker Sack are either the Maine of his adult life or the South Carolina low country of his youth, more often the connection between the two.

So if it’s local color, I like local color, and damn those who don’t. In fact, it’s no secret that I’ve always admired and envied Burroughs, if not felt a kind of kinship with him. We both were born in South Carolina, both graduated as English majors from Sewanee. During my Maymester kayaking and writing course, I taught his book The River Home, which chronicles his canoe trip down the Waccamaw River in the wake of a writer named Nathaniel Holmes Bishop, who made a remarkable 2500 miles journey in a paper canoe from Quebec to the Gulf of Mexico from 1874-1875, and who wrote about it in a book (an obscure one!) called The Voyage of the Paper Canoe.

And, indeed, Burroughs’ prose has an ease to it that can only be described in the metaphorical terms of a river—an ability to flow effortlessly between the personal, the political , the scientific, the historical, the journalistic, the ethical, the philosophical, the etymological, and so forth.[2]

Take, for instance, the first essay in the collection, “A Snapping Turtle in June,” in which Burroughs finds a snapping turtle digging a hole on a road in Maine. The discovery leads him, as writer, into marvelous description:

The shell and skin are a muddy gray; the eye, too, is of a murky mud color. The pupil is black and shaped like a star or a spoked wheel. Within the eye there is a strange yellowish glint, as though you were looking down into turbid water and seeing, in the depths of the water, like light from a smoldering fire. It is one of Nature’s more nightmarish eyes…The snapper’s eye is dull, like a pig’s, but inside it there is this savage malevolence, something suggesting not only an evil intention towards the worlds, but the torment of an inner affliction.

I did not intend, when copying that just now, to quote that much of the text. But each sentence, as you will note, surged with a new intensity.[3]

The literary father here, of course, is Thoreau. One cannot think of a New England nature essayist, even a South Carolina transplant, without thinking of Thoreau, who, more than Emerson, wrote essays that moved so easily between narrative and meditation.

But back to snapping turtles.

It’s not just description that carries this essay—it’s also the fact that Burroughs is a meticulous researcher. And he can relate his research to the non-scientific reader: “The fish they catch by luring them into range with their vermiform tongues, which may have something to do with the role of trickster that they assume in the mythology of North American Indians.”

And then Burroughs will step back and narrate the story of showing the turtle to his young daughters and of carrying the hissing turtle from road to ditch. And then, as though reaching farther down into the croker sack, he’ll pull out the real story—a flashback to his boyhood in Conway, a summer in which he works for a timber company with his two cousins[4].

It’s in this memory that something terrible and strange happens when a drunk—sitting in a country store where the timber crew is having lunch, and mumbling incoherencies about a man named McNair—suddenly explodes and takes out his rage on a snapping turtle that is something like the store’s houseguest:

The turtle seemed weary, deflated, too long out of water. The man nudged its head with his boot, and the turtle hissed and struck feebly toward him. The man glared down at it, letting his rage recover and build back in him. He looked like a diver, gathering to plunge. The turtle’s mouth hung open, when it hissed again the man’s arm suddenly jerked down with the pistol and he shot it, shattering the turtle’s head. ‘That’s what I’d do to that goddamned McNair.’

Burroughs doesn’t end the essay there. He returns, of course, to his daughters, who are made more innocent in contrast with the violent memory. But the episode haunts the reader in a way that it must haunt Burroughs himself, and one sees the very fluid connection between Nature and Human.

I won’t spoil the rest of the essays as I might have here. But it’s fair to say that Burroughs treats the rest of his subjects—moose, fishing, dogs, duck hunting, the croker sack itself—with the same range of complexity and beauty as he does the snapping turtle.

There is, perhaps, a limited readership for a book like this, but I am in it. My interest is partly local, partly personal, but mostly because of the gorgeous writing, both on the sentence and thematic level, that just flows.

At the end of “Of Moose and Moose Hunter,” Burroughs has a kind of flash forward to a moment that hasn’t happened yet, but will, when he sees a moose while fly-fishing, and how he describes it might be exactly how one feels about reading this book:

And I would look up from the water, almost dizzy with staring for so long at nothing but the tiny fly drifting in the current, and there they would be—maybe a cow and a calf—standing on the other bank, watching me watch them, trying to fathom it.

[1] Burroughs: “In South Carolina the word referred to any biggish cloth sack—for example, the hundred-pound sacks that livestock feed came in.”

[2] Burroughs also has an amazing vocabulary that he employs with ease. In one paragraph alone he uses the following words casually and in a way that doesn't suggest, in my opinion, pretense: frowsy, parataxis, importunity, and furtive.

[3] “The image is Zen,” the poet Charles Wright writes. “The metaphor is Christian.” If so (and I do believe so), in the quoted passage above you’ll notice the Zen-like attention to detail but also the subtle ways in which Burroughs converts images to wonderful metaphors. And that, I think, may be a valid way to describe Burroughs as a writer—he never makes any outright statements of faith, but his writing is imbedded with an intellectual Christianity (a.k.a. Episcopalianism).

[4] Burroughs is also, I might add here, a master of character description: “He was lanky, with comically large feet and big, bony, lightly freckled hands and wrists, and you would have expected him to have no strength and stamina at all. But he could use any of the tools we used—bushaxe or machete or grubbing hoe—with no sign of strain or fatigue, all day long, holding the tool gingerly, a pace that the rest of us could not sustain.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed